| Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, ISSN 1923-2861 print, 1923-287X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Endocrinol Metab and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.jofem.org |

Letter to the Editor

Volume 14, Number 2, April 2024, pages 85-88

A Significance of Selective Inhibition of Urate Transporter 1 and Non-Inhibition of Adenosine Triphosphate-Binding Cassette Transporter in Renal Function in a Patient With Advanced Stage Chronic Kidney Disease

Hidekatsu Yanaia, b, Miki Yoshinobua, Hiroki Adachia

aDepartment of Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism, National Center for Global Health and Medicine Kohnodai Hospital, Chiba, Japan

bCorresponding Author: Hidekatsu Yanai, Department of Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism, National Center for Global Health and Medicine Kohnodai Hospital, Ichikawa, Chiba 272-8516, Japan

Manuscript submitted March 7, 2024, accepted March 13, 2024, published online April 16, 2024

Short title: Dotinurad’s Potential to Improve Renal Function in CKD Patient

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jem949

| To the Editor | ▴Top |

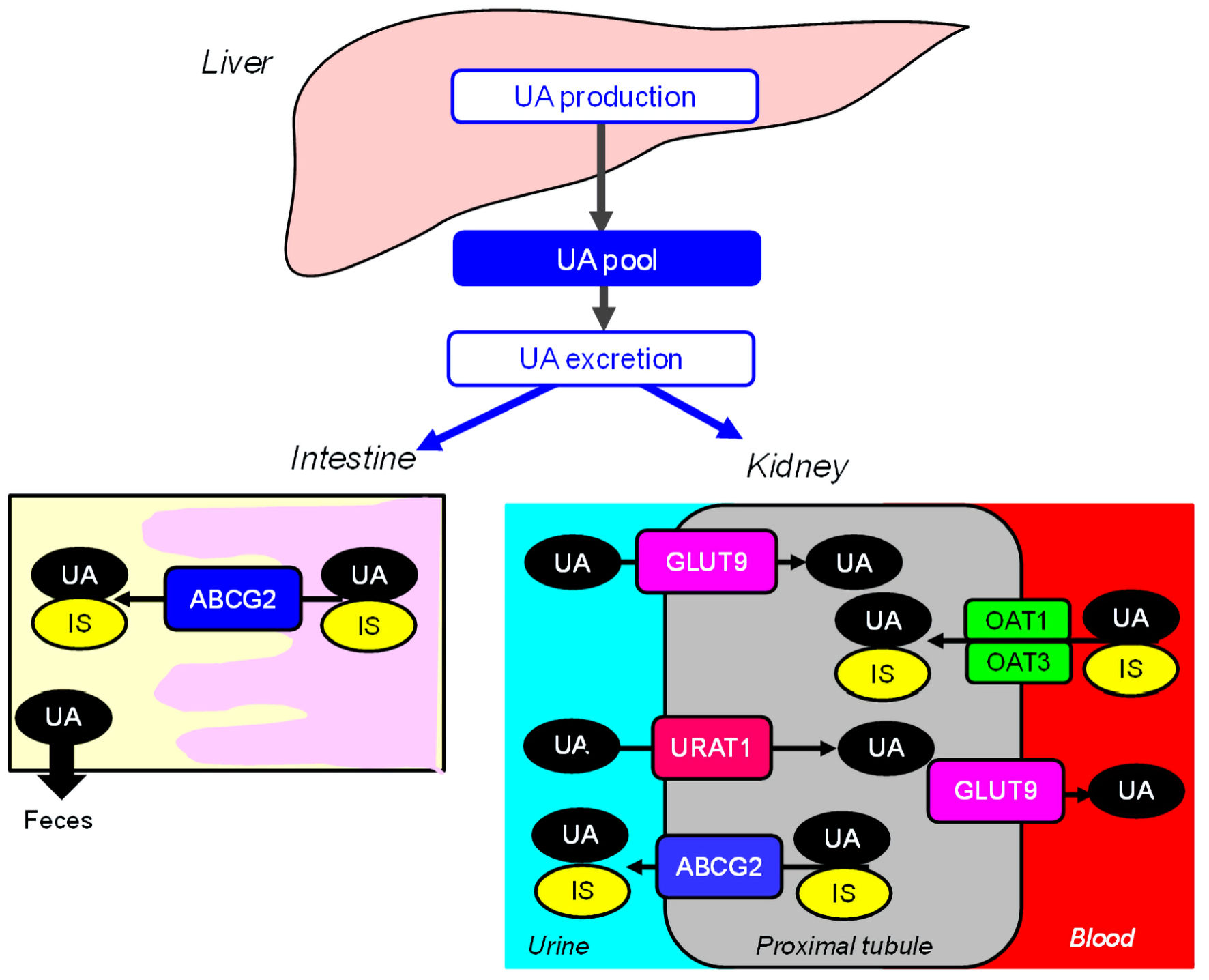

Recently, we proposed our interesting hypothesis on a possible exquisite crosstalk of urate transporter 1 (URAT1) with other uric acid (UA) transporters for chronic kidney disease (CKD) induced by dotinurad [1]. Here, we will report a case that proved our hypothesis. In humans, reabsorption of UA into blood plays a crucial role in regulating serum UA. Renal UA reabsorption is mainly mediated by URAT1 and glucose transporter 9 (GLUT9) [2] (Fig. 1). The adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette transporter G2 (ABCG2) has been identified as a high-capacity UA exporter that mediates renal and extra-renal (intestinal) UA excretion [3] (Fig. 1). Indoxyl sulfate (IS) is an important uremic toxin that accumulates under renal impairment and is involved in the progression of CKD, by inducing inflammation and free radical production [4]. Serum IS levels increase gradually with the decrease of renal function and reached the highest level in CKD stage 5 [5]. IS excretion is mediated by renal and intestinal ABCG2 [6] (Fig. 1). Therefore, as the CKD stage progresses, the function of ABCG2 becomes more important in maintaining renal function.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Renal and intestinal excretion of UA and indoxyl sulfate. ABCG2: ATP-binding cassette transporter G2; GLUT9: glucose transporter 9; IS: indoxyl sulfate; OAT: organic anion transporter; UA: uric acid; URAT1: urate transporter 1; ATP: adenosine triphosphate. |

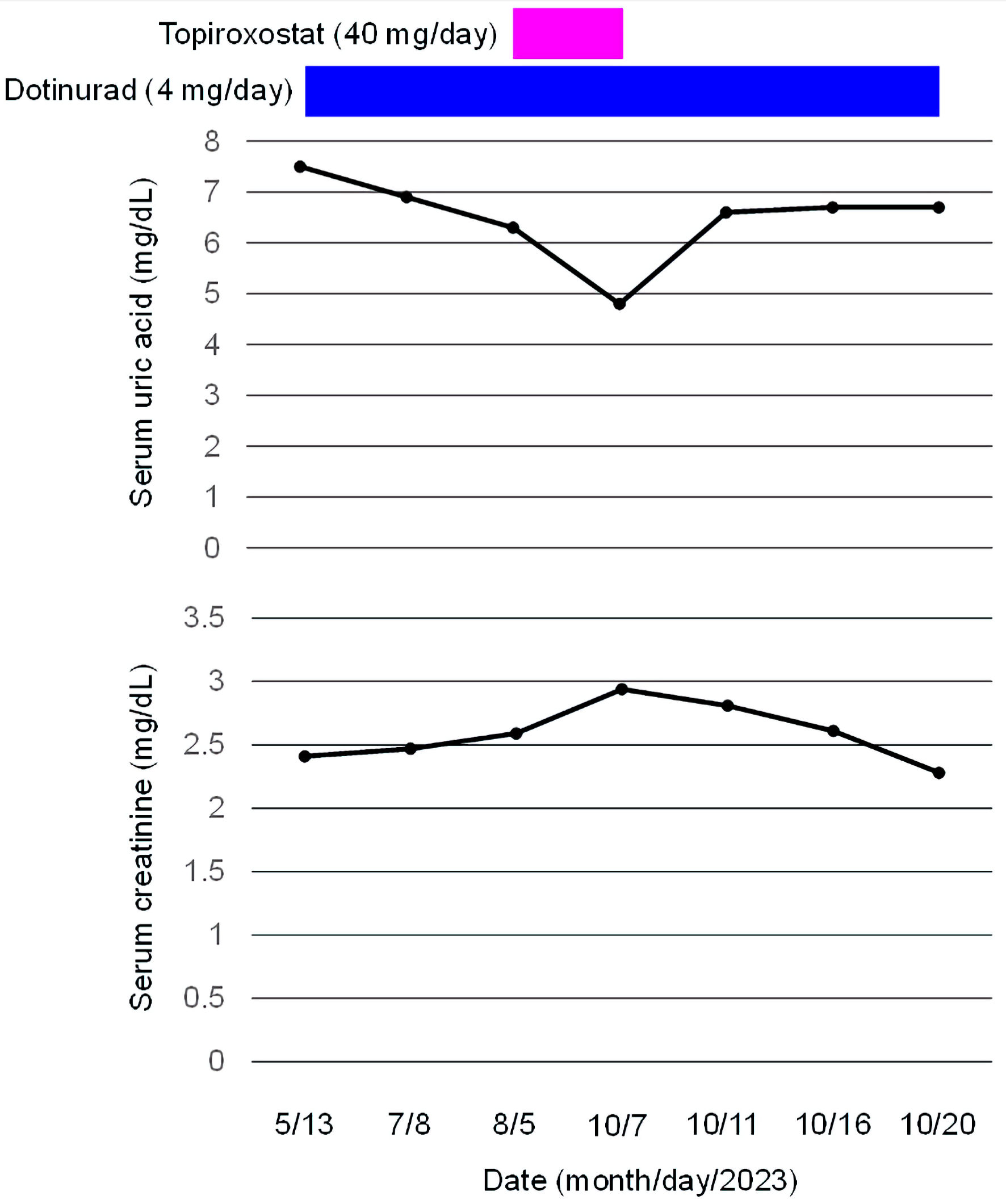

We previously reported that the use of dotinurad, a novel selective URAT1 inhibitor which does not inhibit ABCG2, improved renal function in a 72-year-old male obese diabetic patient with CKD stage G4 [7]. After that, we added a xanthin oxidase (XO) inhibitor, topiroxostat, because the UA-lowering effect of maximal dose of dotinurad was not sufficient. Before the start of topiroxostat, systolic and diastolic blood pressures were 132 and 73 mm Hg, respectively. Serum UA and creatinine levels were 6.3 and 2.59 mg/dL, respectively. Two months after the start of topiroxostat, systolic and diastolic blood pressures were 134 and 72 mm Hg, which did not significantly change as compared with those before the start of topiroxostat. Although serum UA level remarkably decreased from 6.3 to 4.8 mg/dL, serum creatinine level increased from 2.59 to 2.94 mg/dL (Fig. 2). We discontinued the use of topiroxostat due to worsening of renal function.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Change in serum creatinine levels before and after the start of topiroxostat in a diabetic patient who developed CKD stage G4. CKD: chronic kidney disease. |

Four days after the discontinuation of topiroxostat, serum UA level promptly increased to 6.6 mg/dL, however, serum creatinine level promptly decreased to 2.81 mg/dL. Thirteen days after the discontinuation of topiroxostat, serum UA increased to 6.7 mg/dL; however, serum creatinine continued to decrease to 2.28 mg/dL. During the period after the discontinuation of topiroxostat, a significant change in blood pressure was not observed.

Topiroxostat was reported to inhibit ABCG2 [8], which may lead to increase in serum creatinine due to reduced excretion of IS. We previously reported a significant increase in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), in spite of an increase in serum UA, by the switching from fenofibrate which inhibits ABCG2 to pemafibrate in type 2 diabetic patients [8, 9], supporting an importance of ABCG2 for renal function. Hyperuricemia was associated with a greater incidence of end-stage renal disease [10]. Adjusted hazard ratios for hyperuricemia were 2.004 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.904 - 4.444) in men and 5.770 (95% CI: 2.309 - 14.421) in women. UA itself is toxic for kidney; however, in patients with severe renal impairment, IS is also involved in the progression of CKD. Therefore, the function of intestinal ABCG2 which excretes IS into urine may be more critical for renal function in patients with advanced CKD. An oral spherical carbonaceous adsorbent (AST-120, Kremezin; Kureha Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) adsorbs indole, the precursor of IS, in the intestine and prevents IS production. Since AST-120 decreases serum IS in a dose-dependent manner, multicenter prospective trials have been conducted in Japan in the 1980s; these trials were mostly in favor of the efficacy of AST-120 in delaying the initiation of dialysis in patients with advanced stage CKD [11]. This supports the significance of intestinal ABCG2 which excretes IS for the maintenance of renal function in patients with severe renal dysfunction. A very recent study reported that dotinurad did not significantly change eGFR in patients with 30 ≤ eGFR < 45 and eGFR ≥ 45; however, dotinurad significantly improved eGFR in patients with eGFR < 30 [12], supporting our hypothesis.

We have to mention the limitations of our case report. We did not measure serum IS which might have strengthened our hypothesis. We summarized our hypothesis. Dotinurad inhibits the reabsorption of UA, which reduced UA accumulation in the kidney. Since ABCG2 is an exporter of both UA and IS, it is thought that when UA in the kidney decreases, more IS is excreted into urine by ABCG2 because IS has less competition with UA for ABCG2 (Fig. 3a). Topiroxostat inhibits renal ABCG2, and IS is not excreted into the urine and accumulates in the kidney, which may deteriorate renal function (Fig. 3b). Topiroxostat also inhibits intestinal ABCG2, which decreases IS excretion into the feces and increases blood IS, further worsening renal function by increasing renal IS accumulation (Fig. 3b).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Effects of dotinurad (a) and topiroxostat (b) on renal and intestinal transport of UA and indoxyl sulfate, and renal function. ABCG2: ATP-binding cassette transporter G2; IS: indoxyl sulfate; UA: uric acid; URAT1: urate transporter 1. ATP: adenosine triphosphate. |

In conclusion, our case suggests that dotinurad which selectively inhibits URAT1 and does not inhibit ABCG2 may have the potential to improve renal function in patients with severe renal dysfunction because IS excretion by ABCG2 may be very critical for renal function in such patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Division of Research Support, National Center for Global Health and Medicine Kohnodai Hospital.

Financial Disclosure

Authors have no financial disclosure to report.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest concerning this article.

Informed Consent

Informed consent has been obtained from the patient.

Author Contributions

HY designed the research, and MY and HA collected and analyzed data. HY wrote and approved the final paper.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| References | ▴Top |

- Yanai H, Adachi H, Hakoshima M, Katsuyama H. A possible exquisite crosstalk of urate transporter 1 with other urate transporters for chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease induced by dotinurad. Cardiol Res. 2023;14(2):158-160.

doi pubmed pmc - Yanai H, Adachi H, Hakoshima M, Katsuyama H. Molecular biological and clinical understanding of the pathophysiology and treatments of hyperuricemia and its association with metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases and chronic kidney disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(17):9221.

doi pubmed pmc - Matsuo H, Takada T, Ichida K, Nakamura T, Nakayama A, Ikebuchi Y, Ito K, et al. Common defects of ABCG2, a high-capacity urate exporter, cause gout: a function-based genetic analysis in a Japanese population. Sci Transl Med. 2009;1(5):5ra11.

doi pubmed - Barreto FC, Barreto DV, Liabeuf S, Meert N, Glorieux G, Temmar M, Choukroun G, et al. Serum indoxyl sulfate is associated with vascular disease and mortality in chronic kidney disease patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(10):1551-1558.

doi pubmed pmc - Lin CJ, Chen HH, Pan CF, Chuang CK, Wang TJ, Sun FJ, Wu CJ. p-Cresylsulfate and indoxyl sulfate level at different stages of chronic kidney disease. J Clin Lab Anal. 2011;25(3):191-197.

doi pubmed pmc - Taniguchi T, Omura K, Motoki K, Sakai M, Chikamatsu N, Ashizawa N, Takada T, et al. Hypouricemic agents reduce indoxyl sulfate excretion by inhibiting the renal transporters OAT1/3 and ABCG2. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):7232.

doi pubmed pmc - Yanai H, Yamaguchi N, Adachi H. Chronic kidney disease stage G4 in a diabetic patient improved by multi-disciplinary treatments based upon literature search for therapeutic evidence. Cardiol Res. 2022;13(5):309-314.

doi pubmed pmc - Miyata H, Takada T, Toyoda Y, Matsuo H, Ichida K, Suzuki H. Identification of febuxostat as a new strong ABCG2 inhibitor: potential applications and risks in clinical situations. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:518.

doi pubmed pmc - Yanai H, Katsuyama H, Hakoshima M. A significant increase of estimated glomerular filtration rate after switching from fenofibrate to pemafibrate in type 2 diabetic patients. Cardiol Res. 2021;12(6):358-362.

doi pubmed pmc - Iseki K, Ikemiya Y, Inoue T, Iseki C, Kinjo K, Takishita S. Significance of hyperuricemia as a risk factor for developing ESRD in a screened cohort. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(4):642-650.

pubmed - Yamaguchi J, Tanaka T, Inagi R. Effect of AST-120 in chronic kidney disease treatment: still a controversy? Nephron. 2017;135(3):201-206.

doi pubmed - Kurihara O, Yamada T, Kato K, Miyauchi Y. Efficacy of dotinurad in patients with severe renal dysfunction. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2024;28(3):208-216.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism is published by Elmer Press Inc.