| Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, ISSN 1923-2861 print, 1923-287X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Endocrinol Metab and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jofem.org |

Review

Volume 6, Number 1, February 2016, pages 1-11

Therapeutic Methods Against Insulin Resistance

Hernando Rafaela, b

aAcademia Peruana de Cirugia, Lima, Peru

bCorresponding Author: Hernando Rafael, Belgica 411-Bis, Colonia Portales, 03300 Mexico City, Mexico

Manuscript accepted for publication February 17, 2016

Short title: Therapy Against Insulin Resistance

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14740/jem333e

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Hypothalamus and Its Dysfunction

- The Pancreas and Its Dysfunction

- Adipose Tissue and Adipocytokines

- Insulin Receptor

- Insulin Resistance and Its Treatment

- Conclusions

- References

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Clinical, neurosurgical and autopsy findings show that type 2 diabetes mellitus is caused by progressive ischemia in the anterior hypothalamus and endocrine pancreas due to atherosclerosis, and associated with insulin resistance. The hypothalamic ischemia provokes neuroendocrinological disorders through descending projections, and the pancreatic ischemia causes an inappropriate insulin secretion. Both ischemic structures can be improved by means of omental implantation (omental transplantation or transposition) or with anti-inflammatory drugs. Likewise, experimental and clinical observations suggest that insulin resistance is caused by inflammatory action of tumor necrosis factor alpha and resistin in the insulin receptor. Because, in contrast to this, high-dose aspirin or resveratrol can reduce hyperglycemia to normal or near normal in diabetic patients. That is, both drugs are almost specific for the treatment of insulin resistance. Finally, the use of clonazepam at night can have a beneficial effect on glucose homeostasis, because it can reduce the effects of stressful stimuli and normalize the sleep disorders or loss.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes mellitus; Hypothalamic ischemia; Insulin receptor; Insulin resistance; Aspirin; Resveratrol

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Clinical and surgical findings have demonstrated that challenging diseases such as Huntington, Alzheimer, Pick, aging, type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), essential hypertension, Parkinson, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and olivopontocerebellar atrophy (OPCA) are caused by progressive ischemia, due to cerebral atherosclerosis, associated to vascular anomalies [1-8]. Because, in contrast to this, its revascularization by means of an omental transplantation (free graft with vascular microanastomoses) can cure or improve these diseases.

Atherosclerosis, a chronic inflammatory disease in the inner wall of the arteries [9], is initiated in the fetal life due to primary factors (hemodynamic laws) and later on, secondary factors (risk factors such as carbon monoxide, cigarette smoker, organic solvents and insecticides, among others) of sequential appearance in the childhood, adolescence and adult life [10, 11]. Likewise with the age, atherosclerotic changes progress in form of centrifugal from the aortic arc toward the descending aorta, innominate arteries, and its collateral and terminal branches [1, 11].

Up to date, almost all researchers consider that the etiology of type 2 DM is little known. However, unlike other challenging diseases [4, 6], I believe that this disease is initiated in the anterior hypothalamus by ischemia, and years later, continued by pancreatic ischemia and insulin resistance [12-14]. The vascular impairment in the hypothalamus and pancreas can be improved by means of recanalization [15-18] or revascularization [2, 13, 14, 19]; meanwhile, the treatment of insulin resistance continues to be a challenge. Thus, in this review article, I analyze three key factors involved in the pathogenesis of type 2 DM, but especially of insulin resistance.

| Hypothalamus and Its Dysfunction | ▴Top |

A diencephalic structure, the hypothalamus, has a mean height of 10.85 mm (range 5 - 16 mm), a mean anteroposterior diameter of 15 mm (range 10 - 23 mm) [20], and weight about 4 g in the average adult human brain [21]. Therefore, the hypothalamus is rectangular and horseshoe (separated by the III ventricle), with anatomical variations in its size, vascularization, and afferent and efferent projections. The hypothalamic parenchyma is constituted by nuclear groups (about 11 major nuclei) intermingled with bands of unmyelinated and myelinated fibers, especially from the medial temporal lobes [22, 23] and prefrontal limbic areas [5, 24]. Both of them related with sleep disorders [25, 26] and stressful impulses on the hypothalamic nuclei [5, 27-32].

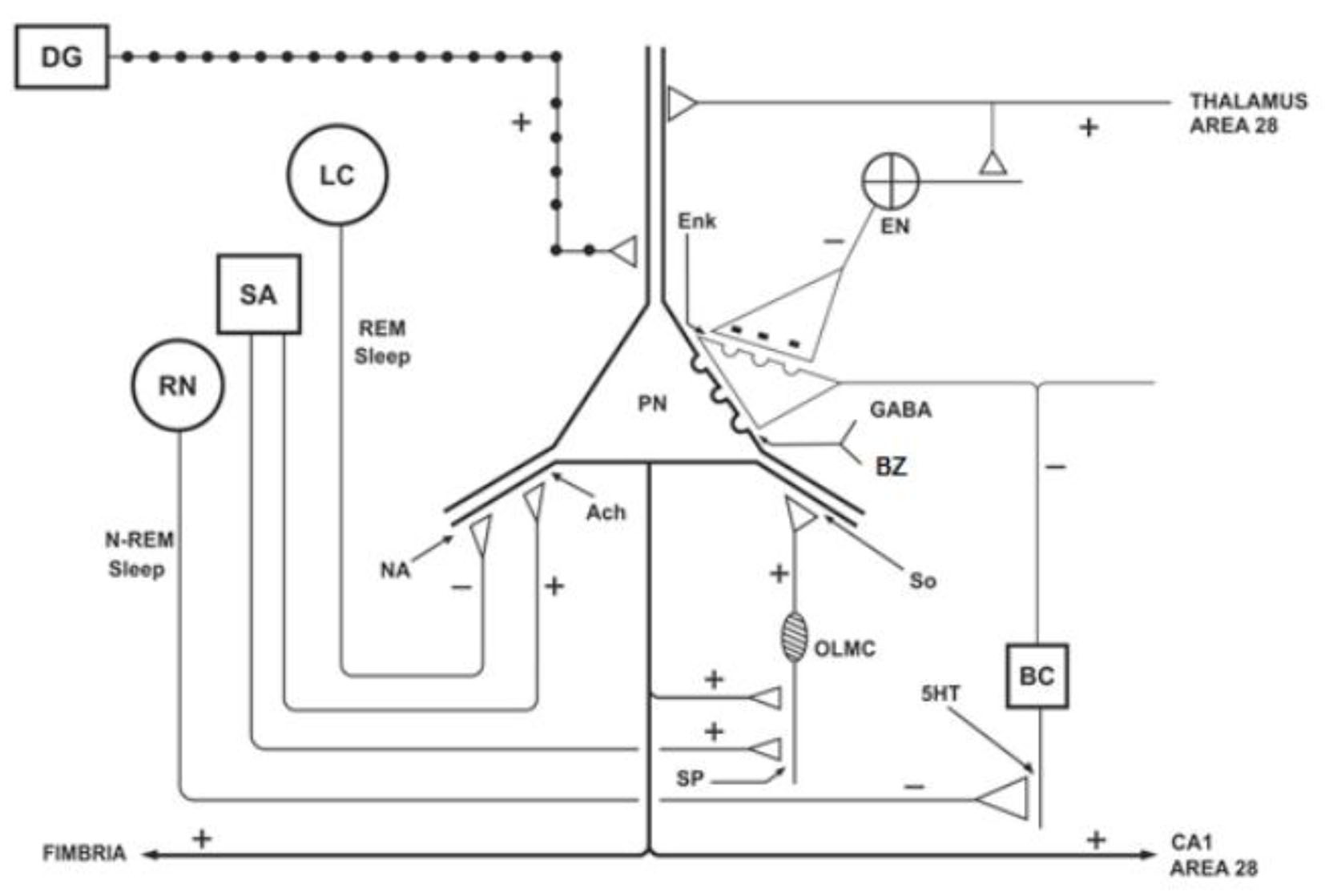

Figure 1 represents the hippocampus, which is located in the medial temporal lobes and is constituted by dentate gyrus and the cornu Ammon with their CA1 to CA4 subdivisions [2, 13, 33, 34]. The hippocampus receives descending afferents from the anterior nuclear complex of the thalamus, entorhinal cortex (area 28) and the amygdala (through alveus) [29, 31], and ascending afferents from the supramammillary nuclei of the hypothalamus, the septum (origin of cholinergic axons), raphe nuclei (origin of serotoninergic axons) and locus coeruleus (origin of noradrenergic axons) [22, 31, 35]. By contrast, the granule neurons of the dentate gyrus send efferent axons (mossy fibers) to finish on the apical dendrites of CA3 pyramidal neurons [22, 35, 30]; whereas the pyramidal neurons from the CA3 subdivision send glutamatergic axons through the fimbria and fornix to finish in the hypothalamus, and other Schaffer collateral axons through the alveus, and they terminate in the CA1 and area 28. However, the greater population of cells in the hippocampus is integrated by interneurons (local circuit neurons), especially the basket cells with GABAergic function on the pyramidal cells [30, 31, 36, 37]. Thus, the hippocampus is anatomically connected to parts of the brain that are involved with learning, short-term memory, emotional behavior, sleep and stress, among other functions [22, 29, 32]. The benzodiazepines (BZ) act on the GABA-BZ receptor complex located on the pyramidal neurons of the cornu Ammon [22, 31].

Click for large image | Figure 1. Schematic representation of the hippocampus, showing the ascending projections originating from the septal area (SA), locus coeruleus (LC) and raphe nuclei (RN), and the action of the benzodiazepines (BZ) on the pyramidal neurons (PNs). DG: dentate gyrus; BC: basket cell; EN: enkephalinergic neuron; Enk: encephalin; OLMC: olm cell; SO: somatostatin; Ach: acetylcholine; NA: noradrenaline; 5HT: serotonin; SP: substance P. Adapted from reference [22]. |

Between 25 and 30 years of age, the cerebral blood flow declines progressivelly to mean value of adults (50 - 55 mL/100 g/min) [3, 33, 38]. Deterioration circulatory coincides with the appearance of atherosclerotic plaques in the supraclinoid carotids [34-36, 39]. Moreover, these plaques located at the mouths of the superior hypophyseal, infundibular and some perforating arteries are responsible for progressive ischemia in the hypothalamus [3, 5, 40, 41]. Therefore, hypothalamic nuclei can suffer different grades of ischemia [4, 5], oxidative stress [6, 42, 43] and hypothalamic autophagy [44].

The hypothalamic dysfunction caused by ischemia in the anterior and middle portions of the hypothalamus is related with the onset of obesity, especially in the preoptic, paraventricular, arcuate, perifornical and ventromedial nuclei [2, 3, 13, 27, 45-47]. At about 30 years of age, this dysfunction is evident and manifested through descending projections [5, 28, 48] such as the hypothalamic-pituitary-somatotropic (HPS), hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA), hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) and the hypothalamic-autonomic-gastroduodenal (HAGD) axes. Therefore, this ischemic process provokes excitation (HPA and HAGD axes) and by contrast, deterioration (HPS and HPG axes) in the nuclei of origin from these descending pathways. Thus, the digestions of proteins, lipids and carbohydrates are favored, and therefore, the plasma levels of glucose, lipids and insulin are increased. Then, these descending pathways are related, in part, with the overweight and obesity [2, 13, 14] and therefore, they provoke the accumulation of fat tissue in the liver, omentum and subcutaneous areas, among other regions. However, hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance have been found also in young lean subjects [46, 47].

In summary, hippocampal and hypothalamic dysfunction is related with the grade of morphological quality, vascular impairment and atherosclerotic changes in the supraclinoid carotids and its branches. Because, in contrast to this, its revascularization by means of omental tissue can improve the function of the medial temporal lobes and residual hypothalamic nuclei [2-5, 19, 41].

| The Pancreas and Its Dysfunction | ▴Top |

The pancreas is a retroperitoneal gland located transversally between L1 and L2 lumbar vertebrae. Its head is attached to the concavity of the duodenum and the tail, close to the spleen. The length of the pancreas is of 20 - 25 cm and weight is between 100 and 150 g, but beginning at the 40 years of age, this gland decreases progressively [49-51].

The exocrine pancreas is constituted by a multitude of acines (acinar tissue) close one another, which determine lobules of 3 - 5 mm each one. The pancreatic secretion produced by the exocrine pancreas is drained in the duodenum through the Wirsung and Santorini ducts [49-51]. This pancreatic secretion is constituted essentially by amylolytic, lipolytic and proteolytic enzymes, among other components [50, 51]. Its insufficiency occurs only when the 85% or more of the pancreas is damaged [14, 50].

The endocrine pancreas is constituted by islets of Langerhans distributed all in the pancreas, but mainly in the tail. In humans, 1 - 2 millons of islets are present in one pancreas and each islet has 2,000 - 3,000 cells arranged in cordons. Each islet contains beta cells (70% of total cells) concentrated at the center, alpha cells (about 20%) at peripheral of the islets, and delta cells (about 5%), G cells (about 1%) and F cells (about 1%) scattered throughout the islets [10, 50, 52]. The beta cells are producing of insulin. Each islet is surrounded by a dense vascular network which penetrates less arteries and arterioles toward the center [49, 51, 52]. The angio-architecture within the islets is very similar to the neuro-vascular relationships in the adrenal medulla, substantia nigra and other monoaminergic nuclei [10, 53]. Therefore, the beta cells receive glucose, oxygen and other nutrients necessary for the synthesis of pro-insulin.

The pancreas receives blood supply from three arteries: hepatic, splenic and inferior pancreatic (branch of the superior mesenteric artery). The two first arteries almost originate from the celiac trunk [49, 54-57], but in about 13% of cases, there are anatomical variants from its origin of these arteries [54, 56-59]. In fetus and childhood, the splenic artery is rectilinear, but then it becomes tortuous with increase of caliber with the age [51, 60]. In its course, this artery emits a series of fine branches to the body and tail of the pancreas. Within the pancreatic parenchyma, there are anastomoses with arterial branches from the inferior pancreatic artery and in rare cases, from the left gastroepiploic artery [59]. In the pancreas, small arteries, arterioles and capillaries surround in form of network to the pancreatic acines, as well as to the islets of Langerhans [10, 51, 52]. That is, normally the islets are highly vascularized.

However, in all people at about 30 years of age and more, we found different grades of atherosclerosis in the thoracic and abdominal aorta, as well as in its collateral branches [1, 12, 60-62]. On a postmortem study of 110 aortas in persons between 28 and 68 years of age, Derrick and colleagues [61] found, in 44% of cases, variable degrees of stenosis by atherosclerotic plaques at the mouths of the celiac trunk, renal and mesenteric arteries. Therefore, since 40 years or more, there is progressive decrease of the blood flow in the pancreas, kidney, liver, biliary system and bowels.

Accordingly, these atherosclerotic plaques located at the mouth of the celiac trunk, associated to anatomical variants from its branches, can provoke progressive ischemia (or abrupt) in the islets and a reduction in the synthesis and release of insulin [12, 14, 52], especially in people with a population of islets within the lower limit of normal, in which the amount of insulin secreted is not sufficient to move glucose into the cell. Then, the use of oral hypoglycemic should not be indicated in advanced stage of type 2 DM.

On the contrary, clinical evidences suggest that, based on the anti-inflammatory, anti-platelet and anti-thrombotic effects of aspirin [18, 63-69], the hypothalamic and pancreatic ischemia can improve by recanalization (increase blood flow to the existing arteries). While an omental transposition (pedicled graft) on the pancreas may be useful against pancreatic ischemia, due to revascularization (formation of new blood vessels), and besides this, provides stem cells from the omentum [14, 70, 71]. I believe that a transplantation of pancreatic islets would not be useful without revascularization.

| Adipose Tissue and Adipocytokines | ▴Top |

There are two types of adipose tissue: brown and white. The brown adipose tissue (BAT) in adult persons is scarce and is located around the adrenal glands, the kidneys, the aorta, mediastinum and neck. The color is due to its rich vascularization and presence of intracellular cytochromes. Whereas the white adipose tissue (WAT) is abundant and is distributed in the liver, omentum, subcutaneous tissue, and in few quantity, in mammary glands, ovaries, cardiac area and orbits, among other zones [51, 71, 72].

Currently, several studies indicate that WAT is an endocrine organ producing numerous proteins with broad biological activity [73-79]. The secretory products of WAT, collectively referred to as adipocytokines (usually abbreviated as adipokines) include about 50 different proteins as [72, 73, 77, 78, 80] leptin, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), interleukin-6 (IL-6), transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), metallothionein, adiponectin, resistin, angiotensinogen, adipsin, acylation stimulating protein (ASP), apelin and visfatin, among other products. In general, serum adipokines levels are related with body mass index (BMI) and there are differences between the WAT of the omentum with the subcutaneous deposits [47, 75]. This WAT can transform the testosterone and androstenedione in estrone and estradiol [71, 81], among other functions.

Within the adipose tissue, in addition to adipocytes, adipokines can also be produced by other cell types as macrophages and immune cells, forming cells the blood vessels [73, 78, 80, 82]. Since the obesity is related with type 2 DM, I describe the function of three adipocytokines involved with this disease.

Leptin

This product was identified in 1994, a peptide hormone secreted principally but no exclusively by adipocytes. Serum leptin levels in normal subjects are of 11.5 (6.35 - 20) ng/mL and in obese adults, 22 (13.5 - 44) ng/mL, i.e., the serum leptin levels are significantly increased in obeses [83]. At the level in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus revascularized by the omentum [5, 19, 84], leptin exerts an inhibitory action on the leptin receptor in the neuropeptide Y (NPY) and Agouti-related protein (AgRP) neurons, and by contrast, proopiomelanocortin (POMC) and cocaine amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) neurons are activated by hormone leptin [74, 79, 85]. In other words, leptin stimulates the anorexigenic pathway and inhibits the orexigenic pathway. Therefore, leptin acts in the arcuate nucleus and adjacent areas to reduce body weight and fat mass [5, 19]. On the contrary, in presence of atherosclerotic plaques at the mouths of the superior hypophyseal, infundibular and in some perforating arteries, the circulating leptin enters little or nothing in the arcuate nucleus [5, 72] and therefore, in obese people, the appetite can continue to be increased by action of orexigenic and ghrelin neural cell of the hypothalamus.

TNF-alpha

In 1993, TNF-alpha was identified as a pro-inflammatory adipocytokine involved in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance [86, 87]. TNF-alpha is a protein secreted by macrophages/vascular endothelial cells in the WAT [69, 73-75], as well as in other inmune cells with a potent inflammatory effect and stimulating the secretion of IL-6, among others [78, 80]. Serum TNF-alpha levels in normal subjects are of 23 (12.5 - 39) pg/mL and in obese adults, 42 (13.8 - 97.5) pg/mL, i.e., serum TNF-alpha levels are significantly high in obeses [74, 75, 83]. However, TNF-alpha levels are also increased in a variety of systemic pathologic conditions, including inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease and cardiac disease [78, 83].

TNF-alpha provokes insulin resistance by interfering with insulin receptor signaling [73, 86, 87, 88] in organs such as liver, muscle and adipose tissue [76, 89]. The targets of TNF-alpha are varied and include immediate (inhibition of insulin-induced insulin receptor and insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1)) phosphorylation [46, 78, 89, 90].

Resistin

Human resistin is a cysteine-rich adipocytokine that induces low-grade inflammatory by stimulating monocytes [91]. Resistin-mediated chronic inflammation can lead to obesity, atherosclerosis, and other cardiometabolic diseases. That is, human resistin is an inflammatory protein [92]. Serum resistin levels in normal and obese adults are similar [83], but not so, in the obese adipose tissue where the resistin is high [74, 75]. Thereby, the circulating glucose concentration is not directly affected by serum resistin in type 2 DM [93].

The resistin is secreted by macrophages, immune cells, mononuclear leukocytes and bone marrow cells [94-96] and it interferes with the activation of IRS-1 [77, 95] and/or adenylyl cyclase-associated protein-1 (CAP-1) [91, 96]. Therefore, resistin causes insulin resistance by dysfunction in the insulin receptor, endothelial cells and smooth muscle. So hyperresistinemia contributes to impaired insulin sensitivity in obese subjects. Thereby, resistin is shown as a pro-inflammatory molecule [74, 92].

In summary, at least three adipocytokines are related with obesity and type 2 DM. Leptin acts directly in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus to provoke a desire to stop eating, through the action of both orexigenic NPY/AgRP and anorexigenic POMC/CART neurons, and moreover, TNF-alpha, resistin and IL-6 interfere with the insulin at grade of its receptor located in the cellular membrane. That is, these three adipokines are, essentially, causes of insulin resistance and by contrast, weight loss can reduce this insulin resistance.

| Insulin Receptor | ▴Top |

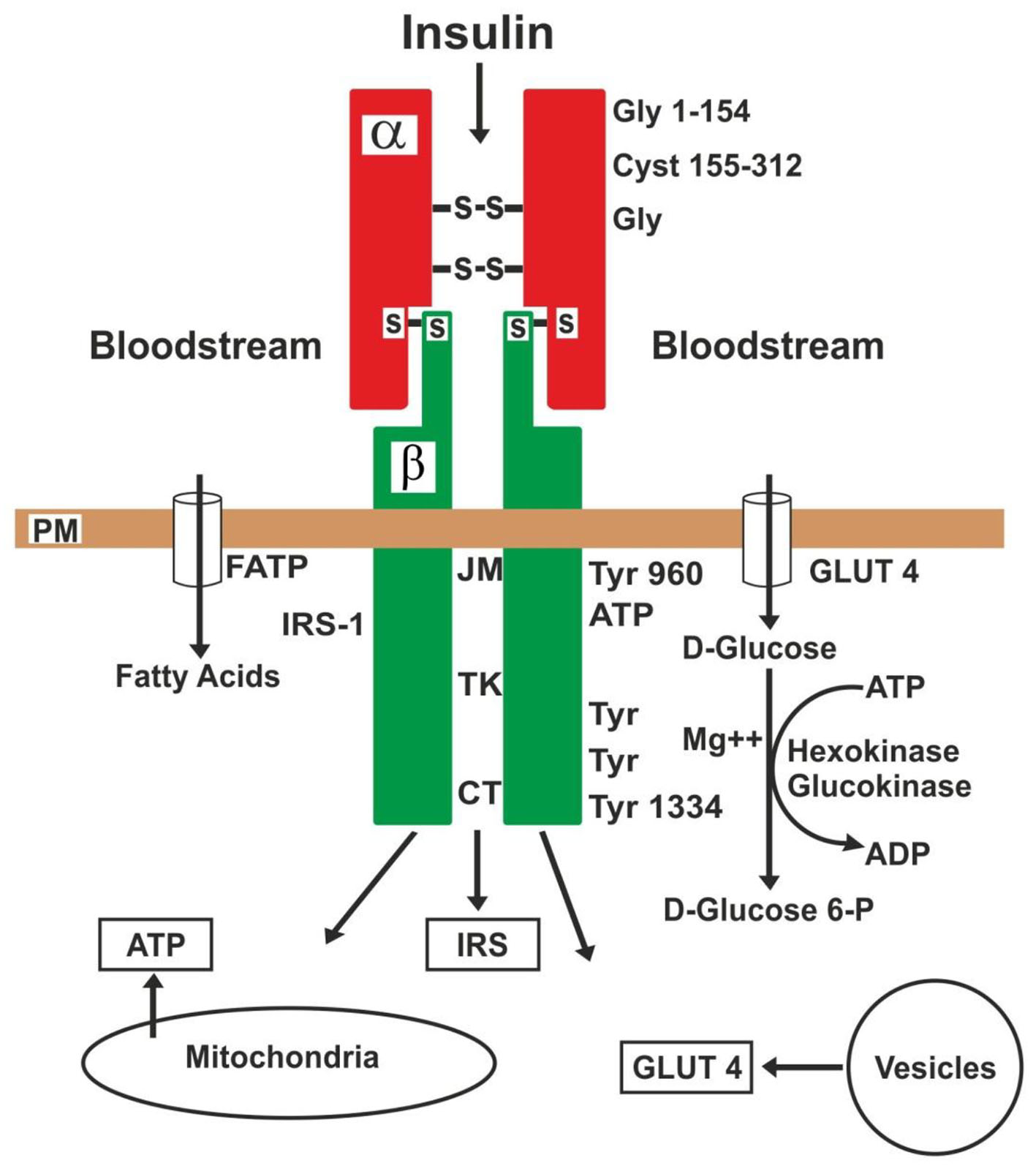

The complete insulin receptor is a heterotetrameric membrane glycoprotein composed of two alpha and two beta subunits, linked together by disulfide bands [97-99]. The two alpha subunits (rich in glycine and cystein) and about one-third of the beta subunits are extracellulars. The rest of the two beta subunits (rich in tyrosine and some remains of serine/threonine) are of transmembrane and intracellular domain [98-101]. The insulin-binding domian is located to the N-terminal (glycine 1-154) of the alpha subunits.

The intracellular region of the beta subunits can be divided into the juxtamembrane (JM), tyrosine kinase (TK) and carboxyl-terminal (CT) domains (Fig. 2). The tyrosine in the possessions 960 is the site of regulation, and in 972 of anchorage and phosphorylation of the IRSs, while the tyrosines in 1003 to 1030 are essential for ligands to the ATP. Moreover, the tyrosines in the possessions 1158 to 1163 are mediators of the activity of tyrosine kinase, and finally, the tyrosines 1328 to 1334 in CT serve to activate other proteins involved in cell proliferation [97-102]. The C-terminal region of IRSs proteins is poorly conserved [101]. Thus, JM and TK domains possess tyrosine phosphorylation sites, enabling them to interact with IRSs (intracellular proteins) [98, 100]. The number of receptors varies from 40 for erythrocytes up to 300,000 for adipocytes and hepatocytes [103] and they are located in almost all the mammalian cells. But more insulin sensitive cells are in the adipocytes, muscle and hepatocytes. So, circulating insulin in the bloodstream is captured by alpha subunits (glycine 1-154) and both of them form a whole to incorporate the D-glucose in the cell of manner indirect through the glucose transporters (GLUTs) [104-109] and after this, the insulin receptor can be desintegrated or return to the cellular surface [97, 100, 105].

Click for large image | Figure 2. Action of insulin on its receptor and substrates. PM: plasma membrane; JM: juxtamembrane; TK: tyrosine kinase; CT: carboxyl-terminal: GLUT4: glucose transporter-4; FATP: fatty acid transporter; IRS: insulin receptor substrate; Gly: glycine; Cyst: cysteine; Tyr: tyrosine. |

Therefore, the first specific event is the binding of insulin to the alpha subunits, which causes a conformational change in the alpha subunits and autophosphorylation in the beta subunits, i.e., this conformational change enables ATP binding (tyrosine 1003 - 1030) to the beta subunits intracellular domain [102, 103]. The ATP binding activates receptor autophosphorylation, which, in turn, enables the receptor’s kinase activity toward intracellular protein substrates [98]. There are numerous autophosphorylation sites in the beta subunits [97, 98, 101]. In other words, the conformational change in the receptor occurs when insulin is united to specific regions of the alpha subunits, and this results in activation of the tyrosine kinase domain [101], to cause the insulin signaling into the cell. Thus, a signal cascade activate: 1) translocation of GLUTs to the plasma membrane and encourage the influx of D-glucose into the cell, 2) the glycogen synthesis, 3) the glycolysis, and 4) the fatty acid synthesis. Fatty acids enter the cell via various fatty acid transporters (FATP-1 to FATP-6) [108, 109]. The GLUTs are released from intracellular vesicles and the ATP, from mitochondria [107-111].

These IRSs are key mediators in the insulin signaling and play a central role in maintaining basic cellular functions such as growth, survival, and metabolism [90, 101, 110]. They act as docking proteins between the insulin receptor and a complex network of intracellular signaling molecules. Four members (IRS-1 to IRS-4) of this family have been identified that differ as to tissue distribution. IRS-1 is the primary cytosolic substrate of the insullin and insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) receptors, and both receptors, leading to the activation of tyrosine kinase in the beta subunits [98, 101, 112]. TNF-alpha decreases the activity of IRSs [88, 99, 100, 106].

The GLUTs are a wide group of membrane proteins [105, 106] that facilitate the transporter of D-glucose over a plasma membrane. These human GLUTs family consist of 14 members (GLUT-1 to GLUT-14) of which 11 have been shown to catalyze sugar transport [106, 108, 111, 112]. For example, GLUT-1 is widely distributed in fetal tissue and in adults, it is expressed in erythrocytes and endothelial cells; GLUT-2 is distributed in renal tubular cells, hepatocytes and pancreatic beta cells; GLUT-3 is in neurons, and GLUT-4 is in adipocytes and striated muscle [106, 107]. At the cell surface, GLUT-4 permits the facilitated diffusion of circulating glucose down its concentration gradient into muscle and fat cells. Once within cells, a small amount of D-glucose is free, the majority is rapidly phosphorylated by glucokinase in the liver and hexokinase in other tissues to form D-glucose-6-phosphate (D-glucose 6-P), where ATP is used as donor of phosphate. So much the glucokinase as hexokinase, both of them need the presence of a divalentcation (Mg++ or Mn++) to form D-glucose-6-P [101, 109]. Therefore, this compound is important at the junction of several metabolic pathways as glycolysis, glyconeogenesis, glycogenesis, glycogenolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway. The oxygen is not necessary for glycolysis, and the presence of oxygen can indirectly suppress glycolysis (Pasteur effect) [101, 107, 113]. By contrast, mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to the development of insulin resistance and may be an effective target for the treatment of insulin resistance [101, 108, 109].

Accordingly, the insulin receptor is a glycoprotein located in the cellular membrane, constituted by two alpha and two beta subunits. Once insulin is captured by the alpha subunits, the receptor experiences a conformational change, and in the final stage, the kinase-mediated signaling cascade stimulates release of GLUTs from microvesicles located in the cytoplasm [109]. Thus, GLUTs are responsible for removing D-glucose from the bloodstream into the cytoplasm [102, 107, 109, 111].

| Insulin Resistance and Its Treatment | ▴Top |

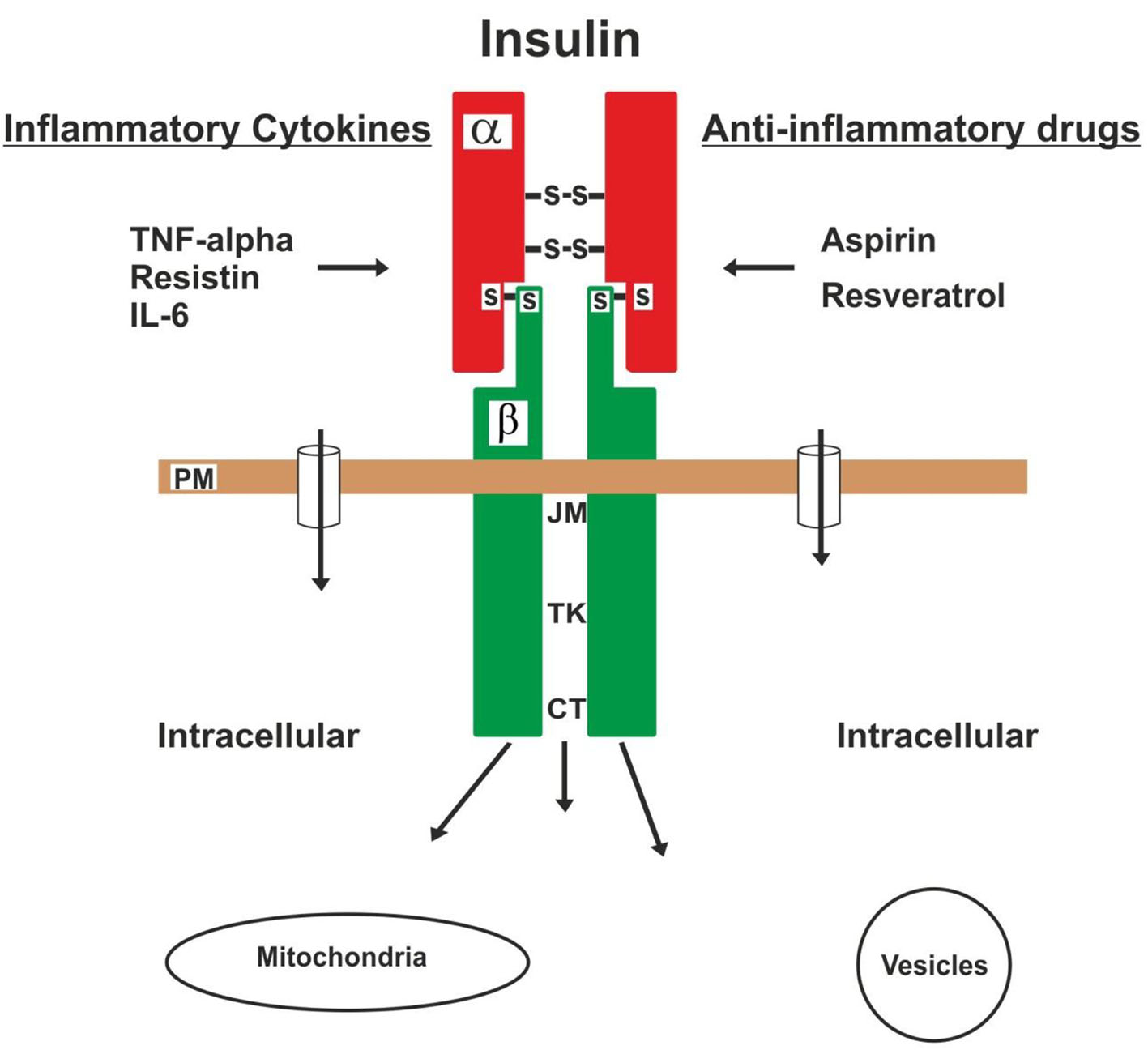

To date, the mechanisms whereby insulin resistance is present in its receptor are still only partially understood. But we know that the insulin resistance is a pathological condition of the receptor which fails to respond to the normal action of the insulin. In other words, the D-glucose does not enter in the cell, after the insulin receptor has been attached. A variety of disorders, acquired and/or genetic, can be associated with the development of insulin resistance and are frequently the result of defects in the structure and function of the receptor [46, 94, 99, 110], originating from hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia.

Normally the insulin receptor is activated by insulin, IGF-I (also known as somatomedin C) and IGF-II [98, 109, 112], and on the contrary, this action is interfered by TNF-alpha, resistin and IL-6, among the main adipokines [73, 77, 78, 87, 88, 91, 93, 95]. Because these adipokines (with potent inflammatory effects) can inhibit the action of the receptor by altering the IRSs activity [77, 90, 95]. Other hormonal antagonists such as cortisol, growth hormone, glucagon and catecholamines are each capable of producing states of insulin resistance. Therefore, anti-inflammatory drugs [64, 65] can reverse or improve this dysfunction of receptor caused by the lipotoxicity of the adipokines [5, 69, 94, 104], as shown in Figure 3. Then, the chronic lipotoxicity of the adipokines in the insulin receptors of obese adults can cause the formation of free radicals, oxidate stress, degeneration and cell death in many cells of the body [4-6, 108]. Type 2 DM in obese children or adolescents, in my opinion, is caused essentially by insulin resistance.

Click for large image | Figure 3. The insulin receptor is injured by inflammatory cytokines, which cause insulin resistance. On the contrary, this injury can be aborted or improved by loss of body fat and the use of anti-inflammatory drugs. |

Earlier reports indicated that high doses of sodium salicylate dramatically reduced glycosuria in diabetes patients [16, 63, 64, 114]. Several years later, other authors [114-116] confirmed that high doses (500 mg or more) of aspirin by 2 - 3 weeks can reduce glycosuria and blood glucose levels in diabetic patients, and in addition to reduced insulin requirements. For these reasons, posterior studies have suggested that an inflammatory process exists in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance [16, 115-117]. Aspirin and sodium salicylate can specifically inhibit IkappaB kinase beta (IKKbeta) activity in vitro and in vivo by binding to IKKbeta to reduce ATP binding. On the contrary, the activity of IKKbeta is stimulated by TNF-alpha and IL-6 [110, 118]. IKKbeta is a serine/threonine protein kinase that phosphorylates the IkappaB protein which is an inhibitor of the transcription factor NF-kappaB complex [110, 114, 116, 118]. The IKKalpha and IKKbeta are two catalytic subunits of the IKK complex. The inhibition of IKKbeta, especially in myeloid cells, may be used to treat insulin resistance [115]. Therefore, this IKKbeta represents a new target for treating insulin resistance, because high-dose aspirin can reverse the damage to the receptor in obesity and type 2 DM by inhibiting IKKbeta activity [16, 115-117, 119, 120].

Basd on the inflammatory effects of TNF-alpha and resistin in the insulin receptor of the cells, clinical evidences [121] have shown that we can utilize also resveratrol (trans-5,3,4-trihydroxystilbene) against insulin resistance. Because this agent increases the activity of superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase, and decreases the plasma levels of TNF-alpha, interferon-gamma, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and pro-inflammatory ILs [122-124]. Especially the plasma levels of TNF-alpha show a significant decrease [123, 125] and so, resveratrol improves this dysfunction of insulin receptor caused by inflammatory adipokines. Some authors [121, 125] have shown that 250 - 500 mg/day of resveratrol by 3 months is effective and provides a potential adjuvant for the treatment of type 2 DM.

Although the mechanism by which the thiazolidinediones (TZDs) exert their effect is not full understood [126], these TZDs are a class of oral antidiabetic drugs that improve metabolic control in patients with type 2 diabetes, because they can reduce insulin resistance in adipose tissue, muscle and the liver [104, 126]. Likewise, TZDs can increase glucose utilization and decrease glucose production. Moreover, insulin resistance induced by TNF-alpha may be partially explained by inhibition of adiponectin secretion, and the resveratrol can prevent this effect of the TNF-alpha. Thus, both of TZDs and the resveratrol may increase the insulin sensitivity and decrease glucose in bloodstream.

Finally, clinical evidence suggests that chronic stress and sleep disorders or loss may be related with increased fatty acids levels, which may partly contribute to insulin resistance [25, 26], due, probably, to a dysfunction of hypothalamus and limbic system caused by ischemia [5, 22, 29]. The clonazepam can improve or abort these sleep disorders and slow or dampen stressful stimuli [22, 32].

| Conclusions | ▴Top |

Based on the above mentioned observations and clinicall results after omental transplantation on the optic chiasma and carotid bifurcation into patients with obesity and type 2 DM, I believe that this disease is initiated at about 30 years of age, in the anterior and middle portions of the hypothalamus, caused by progressive (or abrupt) ischemia, and later is added, vascular impairment in the endocrine pancreas associated to insulin resistance.

This pancreatic ischemia caused by atherosclerotic plaques located at the mouth of the celiac trunk and its branches may be improved through two procedures: first, high-dose aspirin to increase the blood flow (recanalization) in the pancreas and thus, increase insulin secretion, based on its anti-inflammatory, anti-platelet and anti-thrombotic actions [17, 18, 65-68], and second, omental transposition (pedicled graft) on the pancreas in order to revascularize the islets of Langerhans and provide stem cells from the omentum [14, 70, 71]. Through these two procedures, we could improve the function of the exocrine and endocrine pancreas.

Although to date, there is not any method specific for the treatment of insulin resistance, I postulate that this disorder may be improved or aborted by means of three therapeutic procedures: 1) high-dose aspirin; 2) use of resveratrol; and 3) regulation of the stressful stimuli by means of clonazepam. A different conclusion to the therapeutic methods is used by endocrinologists and internists in the management of patients with type 2 DM. However, clinical studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis about our therapeutic suggestion against insulin resistance.

| References | ▴Top |

- Rafael H, Duran MA. Isquemia local por aterosclerosis cerebral como causa de hiertension neurogenica. Rev Mex Cardiol. 2003;14:21-25.

- Rafael H, Mego R, Moromizato P, Garcia W, Rodriguez J. Omental transplantation for type 2 diabetes mellitus; A report of two cases. Case Rep Clin Prac Rev. 2004;5:481-486.

- Rafael H. Rejuvenation after omental transplantation on the optic chiasma and carotid bifurcation. Case Rep Clin Pract Rev. 2006;7:48-51.

- Rafael H, Valadez MT. Hypotalamic revascularization and rejuvenation. J Aging Gerontol. 2014;2:24-29.

- Rafael H. Omental transplantation for neuroendocrinological disorders. Am J Neurodegener Dis. 2015;4(1):1-12.

pubmed - Rafael H. Omental transplantation for neurodegenerative diseases. Am J Neurodegener Dis. 2014;3(2):50-63.

pubmed - Rafael H, Mego R, Peterson PW. Enfermedad de Pick; Un analisis clinico acerca de su etiologia. Acta Med Per. 2012;29(4):197-201.

- Rafael H. Revascularization in some neurodegenerative diseases. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15(4):LE5-6.

pubmed - Ross R. Atherosclerosis - an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):115-126.

doi pubmed - Rafael H. La diabetes mellitus como enfermedad desafiante. Rev Climaterio. 2003;6(36):278-282.

- Rafael H, Ayulo V, Lucar A. Patogenia de la aterosclerosis:Base hemodinamica y factores de riesgo. Rev Climaterio. 2003;6(33):125-128.

- Rafael H, Duran MA, Oviedo I. Isquemia pancreatica por aterosclerosis y diabetes mellitus tipo 2. Rev Climaterio. 2002;5(28):184-187.

- Rafael H. Isquemia hipotalamica por aterosclerosis y diabtes mellitus tipo 2. Rev Climaterio. 2004;7(41):192-197.

- Rafael H. Etiologia y fisiopatologia de la diabetes mellitus tipo 2. Rev Mex Cardiol. 2011;22:39-43.

- Rafael H, Rodriguez J. Drogas anti-inflamatorias no-esteroideas para la hipertension esencial. Rev Fac Med UNAM. 2009;52(5):227-229.

- Hundal RS, Petersen KF, Mayerson AB, Randhawa PS, Inzucchi S, Shoelson SE, Shulman GI. Mechanism by which high-dose aspirin improves glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(10):1321-1326.

doi pubmed - Fernandez-Real JM, Lopez-Bermejo A, Ropero AB, Piquer S, Nadal A, Bassols J, Casamitjana R, et al. Salicylates increase insulin secretion in healthy obese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(7):2523-2530.

doi pubmed - Gagne JJ, Power MC. Anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of Parkinson disease: a meta-analysis. Neurology. 2010;74(12):995-1002.

doi pubmed - Rafael H, Fernandez E, Ayulo V, Davila L. Weight loss following omental transplantationon the anterior perforated space. Case Report Clin Pract Rev. 2003;4:160-162.

- Lang J. Surgical anatomy of the hypothalamus. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1985;75(1-4):5-22.

doi - Eisenman JS, Masland W. The hypothalamus. In, Goldensohn ES, Appel SH. Scientiphic approach to clinical neurology.Vol II. Chapter 107. Philadelphia, Lea & Febiger. 1977:1886-1898.

- Rafael H, Valadez MT. Disfuncion cerebral minima. III: Tratamiento (reporte preliminar). Salud Publ Mex. 1987;29:55-60.

- Rafael H. Nervios craneanos.Tercera edicion. Capitulo 1 y 11. Mexico DF, Editoral Prado. 2009.

- Rempel-Clower NL, Barbas H. Topographic organization of connections between the hypothalamus and prefrontal cortex in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1998;398(3):393-419.

doi - Viera E. La importancia del reloj biologico en el desarrollo de la obesidad y de la diabetes. Diabetologia. 2015;31:60-63.

doi - Broussard JL, Chapotot F, Abraham V, Day A, Delebecque F, Whitmore HR, Tasali E. Sleep restriction increases free fatty acids in healthy men. Diabetologia. 2015;58(4):791-798.

doi pubmed - Rosmond R. Stress induced disturbances of the HPA axis: a pathway to Type 2 diabetes? Med Sci Monit. 2003;9(2):RA35-39.

pubmed - Herman JP, Cullinan WE. Neurocircuitry of stress: central control of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20(2):78-84.

doi - Nigri A, Ferraro S, D'Incerti L, Critchley HD, Bruzzone MG, Minati L. Connectivity of the amygdala, piriform, and orbitofrontal cortex during olfactory stimulation: a functional MRI study. Neuroreport. 2013;24(4):171-175.

doi pubmed - Aimone JB, Li Y, Lee SW, Clemenson GD, Deng W, Gage FH. Regulation and function of adult neurogenesis: from genes to cognition. Physiol Rev. 2014;94(4):991-1026.

doi pubmed - Szilagyi T, Orban-Kis K, Horvath E, Metz J, Pap Z, Pavai Z. Morphological identification of neuron types in the rat hippocampus. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2011;52(1):15-20.

pubmed - Rafael H, Valadez MT. Disfunccion cerebral minima.II : Etiologia y fisiopatologia. Salud Publ Mex. 1986;28(5):495-503.

- Silva AR, Brandao RL, Moraes M. Carotid siphon geometry and variant of the circle of Willis in the origin of carotid aneurysms. Arq Neuro-Psiquiat. 2012;70(12):917-921.

doi - Flora GC, Baker AB, Loewenson RB, Klassen AC. A comparative study of cerebral atherosclerosis in males and females. Circulation. 1968;38(5):859-869.

doi pubmed - Surur A, Camara JP, Salvatierra W, Sanz R, Camavasio N, Videla R, Machi H, et al. Localizacion y frecuencia de placas ateromatosas intracraneales en pacientes mayores de 40 anos. Rev Argent Radiol. 2014;78(4):193-198.

doi - Stein BM, Mc CW, Rodriguez JN, Taveras JM. Postmortem angiography of cerebral vascular system. Arch Neurol. 1962;7:545-559.

doi pubmed - Leao RN, Mikulovic S, Leao KE, Munguba H, Gezelius H, Enjin A, Patra K, et al. OLM interneurons differentially modulate CA3 and entorhinal inputs to hippocampal CA1 neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(11):1524-1530.

doi pubmed - Lassen NA. Cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption in man. Physiol Rev. 1959;39(2):183-238.

pubmed - Baker AB, Resch JA, Loewenson RB. Hypertension and cerebral atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1969;39(5):701-710.

doi pubmed - Rafael H. Therapeutic methods against aging. Turk J Geriatri. 2010;13(29):138-144.

- Rafael H, Mego R, Mejia E, Diaz G. Transplante de epiplon para la hipertension esencial: Caso reportado. Hipertension (Mex). 2002;23(5):4-7.

- Misra MK, Sarwat M, Bhakuni P, Tuteja R, Tuteja N. Oxidative stress and ischemic myocardial syndromes. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15(10):RA209-219.

pubmed - Uttara B, Singh AV, Zamboni P, Mahajan RT. Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative diseases: a review of upstream and downstream antioxidant therapeutic options. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2009;7(1):65-74.

doi pubmed - DeFronzo RA. Insulin resistance, lipotoxicity, type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis: the missing links. The Claude Bernard Lecture 2009. Diabetologia. 2010;53(7):1270-1287.

doi pubmed - Obici S, Feng Z, Arduini A, Conti R, Rossetti L. Inhibition of hypothalamic carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 decreases food intake and glucose production. Nat Med. 2003;9(6):756-761.

doi pubmed - Straczkowski M, Kowalska I, Stepien A, Dzienis-Straczkowska S, Szelachowska M, Kinalska I, Krukowska A, et al. Insulin resistance in the first-degree relatives of persons with type 2 diabetes. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9(5):CR186-190.

pubmed - Ishikawa M, Pruneda ML, Adams-Huet B, Raskin P. Obesity-independent hyperinsulinemia in nondiabetic first-degree relatives of individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 1998;47(5):788-792.

doi pubmed - Veldhuis JD, Keenan DM, Liu PY, Iranmanesh A, Takahashi PY, Nehra AX. The aging male hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis: pulsatility and feedback. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;299(1):14-22.

doi pubmed - Testud L, Latarjet A. Tratado de anatomia humana. Tomo IV. Barcelona, Salvat. 1978:212-682.

- Rudick J. Fisiologia de la secresion pancreatica. Clin Quir Norteamer. 1981;1:45-52.

- Fawcett DW, Bloom and fawcett. A texbook of histology. 12th, ed. New York, Chapman& Hall. 1994;689-703.

- Unger RH, Orci L. Glucagon and the A cell: physiology and pathophysiology (first two parts). N Engl J Med. 1981;304(25):1518-1524.

doi pubmed - Rafael H. Tejidos donadores de catecolaminas; Una revision. Diagnostico (Peru). 1995;34:42-49.

- Petrella S, De Souza CF, Sgrott A, Medeiros GJ, Marques SR, Prates JC. Anatomiy and variations of the celiac trunk. Int J Morphol. 2007;25(2):249-257.

doi - Patten BM. The cardiovascular system. In, Schaeffer JP, ed. Morris human anatomy: A complete systematic treatise.11th, ed. New York, McGraw-Hill. 1953:611-828.

pubmed - Vandamme JP, Bonte J. The branches of the celiac trunk. Acta Anat (Basel). 1985;122(2):110-114.

doi - Ottone NE, Blasi ED, Dominguez ML, Medan CD. Tronco celiaco mesenterico en combinacion con arterias hepaticas aberrantes. Rev Argent Anat Onl. 2012;3:18-21.

- Glenn F, Keefer EB, Speer DS, Dotter CT. Coarctation of the lower thoracic and abdominal aorta immediately proximal to celiac axis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1952;94(5):561-569.

pubmed - Woodburne RT, Olsen LL. The arteries of the pancreas. Anat Rec. 1951;111(2):255-270.

doi - Texon M. The Hemodynamic Concept of Atherosclerosis. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1960;36(4):263-274.

doi - Derrick JR, Pollard HS, Moore RM. The pattern of arteriosclerotic narrowing of the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries. Ann Surg. 1959;149(5):684-689.

doi pubmed - Rafael H. Low-back pain. J Neurosurg: Spine. 2007;7:114-116.

doi - Williamson RT. On the Treatment of Glycosuria and Diabetes Mellitus with Sodium Salicylate. Br Med J. 1901;1(2100):760-762.

doi pubmed - Reid J, Macdougall AI, Andrews MM. Aspirin and diabetes mellitus. Br Med J. 1957;2(5053):1071-1074.

doi pubmed - Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, Emberson J, Godwin J, Peto R, Buring J, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1849-1860.

doi - Pawar D, Shahani S, Maroli S. Aspirin - the novel antiplatelet drug. Hong Kong Med J. 1998;4(4):415-418.

pubmed - Doutremepuich C, Aguejouf O, Desplat V, Duprat D, Eizayaga FX. Thrombotic events associated to aspirin therapy. Thrombosis. 2012;2012:247363.

doi pubmed - Starke RM, Chalouhi N, Ding D, Hasan DM. Potential role of aspirin in the prevention of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;39(5-6):332-342.

doi pubmed - Carriba P, Comella JX. Neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation: two processes, one target. Neural Regen Res. 2015;10(10):1581-1583.

pubmed - Garcia-Gomez I, Goldsmith HS, Angulo J, Prados A, Lopez-Hervas P, Cuevas B, Dujovny M, et al. Angiogenic capacity of human omental stem cells. Neurol Res. 2005;27(8):807-811.

doi pubmed - Rafael H. Aplicacion clinica del epiplon en el sistema nervioso central. Acta Med Per. 2008;25(3):176-180.

- Chaldakov GN, Stankulov IS, Hristova M, Ghenev PI. Adipobiology of disease: adipokines and adipokine-targeted pharmacology. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9(12):1023-1031.

doi pubmed - Beltowski J. Adiponectin and resistin - new hormones of white adipose tissue. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9(2):RA55-61.

pubmed - Galic S, Oakhill JS, Steinberg GR. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;316(2):129-139.

doi pubmed - Ouchi N, Ohashi K, Shibata R, Murohara T. Adipocytokines and obesity-linked disorders. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2012;74(1-2):19-30.

pubmed - Beltowski J. Apelin and visfatin: unique "beneficial" adipokines upregulated in obesity? Med Sci Monit. 2006;12(6):RA112-119.

pubmed - Gerrits AJ, Gitz E, Koekman CA, Visseren FL, van Haeften TW, Akkerman JW. Induction of insulin resistance by the adipokines resistin, leptin, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and retinol binding protein 4 in human megakaryocytes. Haematologica. 2012;97(8):1149-1157.

doi pubmed - Tsao TS, Hug Ch, Lodish HF. Adipokines: Regulator of metabolic integration and energy metabolism. In, Le Roith D, Taylor SI, Olefsky JM. Diabetes mellitus :A fundamental and clinical text. 3rd edition. Part VI. Chapter 65. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2004:963-977.

- Codoner-Franch P, Alonso-Iglesias E. Resistin: insulin resistance to malignancy. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;438:46-54.

doi pubmed - Acosta E. Obesidad, tejido adiposo y resistencia a la insulina. Acta Bioq Clin Latinoamer. 2012;46(2):183-194.

- Sieminiska L, Wojciechowska C, Swietochowska E, Marek B, kos-Kudla B, Kajdaniuk D, Kajdaaniud D, et al. Serum free testosterona in men with coronary artery aterosclerosis. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9(5):CR162-166.

- Jamaluddin MS, Weakley SM, Yao Q, Chen C. Resistin: functional roles and therapeutic considerations for cardiovascular disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165(3):622-632.

doi pubmed - Mahadik SR, Deo SS, Mehtalia SD. Role of adipocytokines in Insulin resistance; Sudies from urban western indian population. Int J Diabetes Metabol. 2010;18:35-42.

- Munzberg H, Jobst EE, Bates SH, Jones J, Villanueva E, Leshan R, Bjornholm M, et al. Appropriate inhibition of orexigenic hypothalamic arcuate nucleus neurons independently of leptin receptor/STAT3 signaling. J Neurosci. 2007;27(1):69-74.

doi pubmed - Wang Q, Liu C, Uchida A, Chuang JC, Walker A, Liu T, Osborne-Lawrence S, et al. Arcuate AgRP neurons mediate orexigenic and glucoregulatory actions of ghrelin. Mol Metab. 2014;3(1):64-72.

doi pubmed - Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science. 1993;259(5091):87-91.

doi pubmed - Hotamisligil GS, Spiegelman BM. Tumor necrosis factor alpha: a key component of the obesity-diabetes link. Diabetes. 1994;43(11):1271-1278.

doi - Stephens JM, Lee J, Pilch PF. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes is accompanied by a loss of insulin receptor substrate-1 and GLUT4 expression without a loss of insulin receptor-mediated signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(2):971-976.

doi pubmed - Chiu SL, Cline HT. Insulin receptor signaling in the development of neural structures and function. Neural Develop. 2010;5:7.

doi pubmed - Folli F, Bonfanti L, Renard E, Kahn CR, Merighi A. Insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) distribution in the rat central nervous system. J Neurosci. 1994;14(11 Pt 1):6412-6422.

pubmed - Lee S, Lee HC, Kwon YW, Lee SE, Cho Y, Kim J, Kim JY, et al. Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 1 is a receptor for human resistin and mediates inflammatory actions of human monocytes. Cell Metab. 2014;19(3):484-497.

doi pubmed - Suragani M, Aadinarayana VD, Pinjari AB, Tanneeru K, Guruprasad L, Banerjee S, Pandey S, et al. Human resistin, a proinflammatory cytokine, shows chaperone-like activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(51):20467-20472.

doi pubmed - Sokhanguei Y, Eizadi M, Goodarzi MT, Khoshidi D. Association of adipokine resistin with homeostasis model assiesment of Insulin resistance in type II diabetes. Avicenna J Med Biochem. 2015;3:e26467.

doi - Lukman S, Al Safer H, Lee SM, Sim K. Harnessing structural data of Insulin and Insulin receptor for therapeutic designs. J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;5(5):273-283.

doi - Barnes KM, Miner JL. Role of resistin in insulin sensitivity in rodents and humans. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2009;10(1):96-107.

doi - McTernan CL, McTernan PG, Harte AL, Levick PL, Barnett AH, Kumar S. Resistin, central obesity, and type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2002;359(9300):46-47.

doi - Lee J, Pilch PF. The insulin receptor: structure, function, and signaling. Am J Physiol. 1994;266(2 Pt 1):C319-334.

pubmed - Kido Y, Nakae J, Accili D. Clinical review 125: The insulin receptor and its cellular targets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(3):972-979.

pubmed - Becker AB, Roth RA. Insulin receptor structure and function in normal and pathological conditions. Annu Rev Med. 1990;41:99-115.

doi pubmed - Cruz M, Velasco E, Kumate J. [Intracellular signals involved in glucose control]. Gac Med Mex. 2001;137(2):135-146.

pubmed - Sick Y. The Insulin signaling network and Insulin action. In, LeRoith H, Taylor SI, Olefsky JM (eds). Third edition. Chapter 15. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2004:225-244.

pubmed - Olivares JA, Arellano A. Bases moleculares de las acciones de la insulina. REB. 2008;27:9-18.

- Watanabe M, Hayasaki H, Tamayama T, Shimada M. Histologic distribution of insulin and glucagon receptors. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1998;31(2):243-256.

doi pubmed - Maeda N, Takahashi M, Funahashi T, Kihara S, Nishizawa H, Kishida K, Nagaretani H, et al. PPARgamma ligands increase expression and plasma concentrations of adiponectin, an adipose-derived protein. Diabetes. 2001;50(9):2094-2099.

doi pubmed - Diaz DP, Burgos LC. Como se transporta la glucosa a traves de la membrana celular? Iatreia (Colom). 2002;15(3):179-189.

- Scheepers A, Joost HG, Schurmann A. The glucose transporter families SGLT and GLUT: molecular basis of normal and aberrant function. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2004;28(5):364-371.

doi pubmed - Castrejon V, Carbe R, Martinez M. Mecanismos moleculares que intervienen en el transporte de la glucosa. REB. 2007;26(2):49-57.

- Montgomery MK, Turner N. Mitochondrial dysfunction and insulin resistance: an update. Endocr Connect. 2015;4(1):R1-R15.

doi pubmed - Harris RA. Carbohydrate metabolism . I:Major metabolic pathways and their control. In, Devlin TM (ed). Texbook of biochemistry with clinical correlations. Fiftth edition. Chapter 14. New York, John Wiley-Liss. 2002:597-605.

- Lanzerstorfer P, Yoneyama Y, Hakuno F, Muller U, Hoglinger O, Takahashi S, Weghuber J. Analysis of insulin receptor substrate signaling dynamics on microstructured surfaces. FEBS J. 2015;282(6):987-1005.

doi pubmed - Medina RA, Owen GI. Glucose transporters: expression, regulation and cancer. Biol Res. 2002;35(1):9-26.

doi pubmed - Thorens B, Mueckler M. Glucose transporters in the 21st Century. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298(2):E141-145.

doi pubmed - Augustin R. The protein family of glucose transport facilitators: It's not only about glucose after all. IUBMB Life. 2010;62(5):315-333.

doi - Gilgore SG. The influence of salicylate on hyperglycemia. Diabetes. 1960;9:392-393.

doi - Arkan MC, Hevener AL, Greten FR, Maeda S, Li ZW, Long JM, Wynshaw-Boris A, et al. IKK-beta links inflammation to obesity-induced insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2005;11(2):191-198.

doi pubmed - Yuan M, Konstantopoulos N, Lee J, Hansen L, Li ZW, Karin M, Shoelson SE. Reversal of obesity- and diet-induced insulin resistance with salicylates or targeted disruption of Ikkbeta. Science. 2001;293(5535):1673-1677.

doi pubmed - Shoelson SE, Lee J, Yuan M. Inflammation and the IKK beta/I kappa B/NF-kappa B axis in obesity- and diet-induced insulin resistance. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(Suppl 3):S49-52.

doi pubmed - Woronicz JD, Gao X, Cao Z, Rothe M, Goeddel DV. IkappaB kinase-beta: NF-kappaB activation and complex formation with IkappaB kinase-alpha and NIK. Science. 1997;278(5339):866-869.

doi pubmed - Meng Q, Cai D. Defective hypothalamic autophagy directs the central pathogenesis of obesity via the IkappaB kinase beta (IKKbeta)/NF-kappaB pathway. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(37):32324-32332.

doi pubmed - Hammodi SH, Al. Ghandi SS,Yassien AI, Al-Hassani SD. Aspirin and blood glucose in Insulin resistance. Open J Endocr Metabol Dis. 2012;2(2):16-26.

doi - Bhatt JK, Thomas S, Nanjan MJ. Resveratrol supplementation improves glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutr Res. 2012;32(7):537-541.

doi pubmed - Martin AR, Villegas I, Sanchez-Hidalgo M, de la Lastra CA. The effects of resveratrol, a phytoalexin derived from red wines, on chronic inflammation induced in an experimentally induced colitis model. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147(8):873-885.

doi pubmed - Abdallah DM, Ismael NR. Resveratrol abrogates adhesion molecules and protects against TNBS-induced ulcerative colitis in rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;89(11):811-818.

pubmed - Timmers S, Konings E, Bilet L, Houtkooper RH, Van de Weijer T, Goossens GH, Hoeks J, et al. Caloric restriction-like effects of 30 days of resveratrol suplementation on energy metabolism and metabolic profile in obese humans. Cell Metab. 2011;14(5):612–622.

doi - Faghizadeh F, Adibi P, Rafiel R, Hekmatdoost A. Resveratrol suplementation improves inflammatory biomarkers in patentes with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutr Res. 2014;34:837-843.

doi pubmed - McGrane D, Fisher M, McKay GA. Drugs for diabetes: Part 3 thiazolidinediones. Br J Cardiol 2011;18:24-27

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism is published by Elmer Press Inc.