| Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, ISSN 1923-2861 print, 1923-287X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Endocrinol Metab and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jofem.org |

Review

Volume 1, Number 3, August 2011, pages 97-100

Pheochromocytoma, the Challenge to Anesthesiologists

Rudin Domia, b, Hektor Sulaa

aUniversity Hospital Center “Mother Theresa” Tirana, Albania

bCorresponding author: Rudin Domi, Department of Anesthesia, Intensive Care, Emergency and Toxicology, University Hospital Center “Mother Theresa”, Str Rruga e Dibres, 370, Tirana, Albania

Manuscript accepted for publication July 7, 2011

Short title: Pheochromocytoma and Anesthesiologist

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jem27w

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Diagnosis

- Preoperative Preparation and Evaluation

- Intraoperative Management

- Postoperative Considerations

- References

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Once the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma is made, the tumor must be localized and pre-treated before surgical resection. The operation is usually delayed until hypertension is controlled. A good preoperative preparation including also hormonal evaluation, careful and smooth induction of anaesthesia, good collaboration between the surgeon and anaesthesiologist, and finally taking care in the postoperative period, are the most important steps of the treatment. These are also the focus data, mentioned by several authors in their papers regarding the successful treatment of pheochromocytoma, considered as a challenge to the anaesthesiologist.

Keywords: Adrenal gland; Pheochromocytoma; α-blocking agents

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Pheochromocytoma is a neuroendocrine tumor arising from chromaffin cells in the adrenal medulla causing less than 0.1% of all cases of hypertension [1-3]. Usually, tumors are benign but in 10% of the cases it may be malignant. These tumors may secrete the catecholamines (dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine) which explain all the clinical manifestations of the tumors. In rare cases there are neuroendocrine chromaffin tumors that arise outside of the adrenal medulla referred as paragangliomas.

This tumor is occasionally familiar or part of the multiple endocrine adenoma typeIIa or type IIb. Type IIa consists in medullary carcinoma of the thyroid, parathyroid adenoma or hyperplasia, and pheochromocytoma. Type IIb is pheochromocytoma in association with phakomatoses such as von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis and von Hippel-Lindau disease [2].

The clinical manifestations of a pheochromocytoma depend on the profile of catecholamine secretion: If the tumor secretes norepinephrine, clinical picture is associated with hypertension. If epinephrine is the major secreted catecholamine, tachycardia, tachydysrhythmias and hypotension often result.

Pheochromocytoma presents a great challenge to the anesthesiologist, referring to differential diagnosis and the clinical features as hypertension, tachycardia and dysrhythmias, cardiac ischemia or myocardial dysfunction, hyperglycemia, intravascular volume depletion, and lactic acidosis. Twenty-five percent to 50% of hospital deaths in patients with pheochromocytoma occur during induction of anaesthesia or during operative procedures for other causes [2, 4].

| Diagnosis | ▴Top |

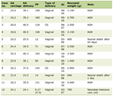

Diagnosis is based on clinical manifestations (excessive sweating; headache; hypertension; orthostatic hypotension; previous hypertensive or arrhythmic response to induction of anaesthesia or to abdominal examination; paroxysmal attacks of sweating, headache, tachycardia, and hypertension; glucose intolerance; polycythemia; weight loss; and psychological abnormalities), on MRI, CT, and finally in laboratory examinations [5] (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Characteristics of Tests for Pheochromocytoma [2] |

| Preoperative Preparation and Evaluation | ▴Top |

A patient with a known pheochromocytoma scheduled for tumor resection undergoes intensive preoperative medical pretreatment. The main problems are as follows [1-3, 5-8]:

1. Medical control of blood pressure;

2. Correction of intravascular volume;

3. Assessment of end-organ consequences of the disease (e.g., cardiomyopathy);

4. Normalization of glucose and electrolyte levels;

5. Hormonally evaluation of the patient.

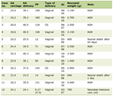

The aims of preoperative preparation are to prevent an acute hypertensive crisis in the operating room and then to minimize catecholamine induced hemodynamic changes during anesthesia and surgery. The preoperative evaluation (Table 2) and adequate preparation is defined when systemic blood pressure is below 160/90mmHg, no orthostatic hypotension, no ventricular premature beats and changes in ST morphology.

Click to view | Table 2. Preoperative Evaluation of Patients With Pheochromocytoma |

Regarding the elevated blood pressure several regimens have been reported in the preoperative period. Phenoxybenzamine,a nonselective, noncompetitive, long acting α-adrenergic blocker for many years has been a mainstay of therapy [1-11].Because some patients may be very sensitive to the effects of phenoxybenzamine, it should be given initially in doses of 20 to 30 mg/70 kg orally once or twice a day. Most patients usually require 60 to 250 mg/day. The efficacy of therapy should be judged by the reduction of symptoms (especially sweating) and stabilization of BP. The optimal duration of α-blockade therapy may lasts from 3 days to 2 weeks. Because of its prolonged effect on α-receptors, it has been recommended to discontinue it 24 to 48 hours before surgery, in order to avoid refractory or severe hypotension after the adrenal gland has been removed. Short-acting, selective, competitive α1-adrenergic receptors blockers (e.g.,doxazosin 2 - 6 mg daily ) have been used to prepare patients for surgery [2, 5, 8, 10-12]. A potential advantage of competitive, selective α1-blockade is that, once the tumor has been resected and excess catecholamine release eliminated, α-adrenergic receptors return quickly to normal function, leading to less hypotension. In our institution, during the period2006 - 2009 we have performed 19 open adrenalectomy cathecholamine secreting hormones. We preferred always Doxazosin for preoperative treatment. Tachycardia as a consequence of elevated catecholamine levels must be treated with β-blockers. The β-blockade must not be instituted before initiation of α-blockade so that α-adrenergic activation would be unopposed in the vasculature. Propranolol, a no selective β1, 2-blocker with a half-life greater than 4 hours, is most frequently used. Most patients require 80 to 120 mg/day. Some patients with epinephrine-secreting pheochromocytomas, may need doses up to 480 mg/day. Other drugs, including prazosin, calcium channel blocking drugs [13], magnesium [14-16], clonidine and dexmedetomidine [17], have also been used to achieve suitable degrees of α-adrenergic blockade before surgery. The combination of Doxazosin with a calcium channel blocker (verapamil 120 - 240 mg every day or nifedipine 30 - 90 mg every day) is an effective combination for resistant cases.

| Intraoperative Management | ▴Top |

Laparoscopy remains gold standard, having some advantages to open surgery, except paragaglionomas resection [5, 9, 18].

Invasive monitoring and central vein access is crucial. The use of all the drugs that increase sympathetic tone, like ketamine, ephedrine, pancuronium, desflurane, must be avoided.

Anesthesia induction and tracheal intubation must be smooth in order to avoid hypertension and tachycardia. Several drugs or techniques are proposed to blunt sympathetic response such as: opioids, esmolol, nicardipine, nitroprusside, nitroglycerin, magnesium sulfate, fenoldopam, urapidil [11].

During the surgical manipulations, brisk hemodynamic changes may happen. The hypertension control is often attained by nitropruside, nicardipine, propofol, nitroglycerine, magnesium and/or by deepening the anesthesia. Tachydisrythmias are often controlled by β-adrenergic blocking agents like esmolol, metoprolol.

Volume depletion correction is important and it is performed by infusion of crystalloids or colloids.

After the adrenal gland has been removed, the hypotension may be severe and it can be controlled by epinephrine, norepinephrine, dopamine or vasopressin [19], especially in the patients receiving phenoxybenzamine.

| Postoperative Considerations | ▴Top |

Postoperative care remains crucial and is focused on metabolic changes like hyperglycaemia and decreased cortisol level, pain treatment and residual postoperative hypertension [8, 13, 19]. The differential diagnosis for persistent hypertension includes a missed pheochromocytoma, surgical complications with subsequent renal ischemia, and underlying essential hypertension.

In addition to the reduction in plasma catecholamines and third-space fluid losses, the residual effects of phenoxybenzamine and α-methylparatyrosine, secondary to long half-lives, are present for up to 36 hours. Thus the hypotension may be present. Vasopressor therapy may be necessary if hypotension occur. Steroid supplementation is necessary for patients who had bilateral adrenalectomies or if hypoadrenalism is suspected.

The need for controlled ventilation is dictated by the extent of surgery, the site of surgery, and the patient’s medical condition.

Aggressive postoperative acute pain treatment is essential. Pain relieving reduce pulmonary and thromboembolic events, the likelihood of residual hypertension, and enhance the quality of life in the early postoperative period.

After the patient discharged, he must be referred to an endocrinologist for further follow-up.

| References | ▴Top |

- Prys-Roberts C. Phaeochromocytoma—recent progress in its management. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85(1):44-57.

pubmed doi - Pauker SG, Kopelman RI. Interpreting hoofbeats: can Bayes help clear the haze? N Engl J Med. 1992;327(14):1009-1013.

pubmed doi - Lenders JW, Eisenhofer G, Mannelli M, Pacak K. Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet. 2005;366(9486):665-675.

pubmed doi - Sutton MG, Sheps SG, Lie JT. Prevalence of clinically unsuspected pheochromocytoma. Review of a 50-year autopsy series. Mayo Clin Proc. 1981;56(6):354-360.

pubmed - Peterfreund R, Lee S. Endocrine surgery and intraoperative management of endocrine conditions. In Longnecker Anesthesiology Mc Graw-Hill 2008, 1433-36.

- Scherpereel P. Critical Care Focus Volume 4: Endocrine disturbance. European Journal of Anaesthesiology 2001, 18: 417.

- Roizen M, Fleisher L. Anesthesia and implications of concurrent disease. In Miller Anesthesia 7 th Ed. Churchill-Livinstone 2009: 1084-85.

- Morgan E,Mikhail M, Murray M. Anesthesia for the patients with Endicrine disease.Clinical Anesthesiology 2006: 812-3.

- Witteles RM, Kaplan EL, Roizen MF. Safe and cost-effective preoperative preparation of patients with pheochromocytoma. Anesth Analg. 2000;91(2):302-304.

pubmed - Tauzin-Fin P, Sesay M, Gosse P, Ballanger P. Effects of perioperative alpha1 block on haemodynamic control during laparoscopic surgery for phaeochromocytoma. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92(4):512-517.

pubmed doi - Kinney MA, Narr BJ, Warner MA. Perioperative management of pheochromocytoma. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2002;16(3):359-369.

pubmed doi - Prys-Roberts C, Farndon JR. Efficacy and safety of doxazosin for perioperative management of patients with pheochromocytoma. World J Surg. 2002;26(8):1037-1042.

pubmed doi - Lebuffe G, Dosseh ED, Tek G, Tytgat H, Moreno S, Tavernier B, Vallet B, et al. The effect of calcium channel blockers on outcome following the surgical treatment of phaeochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Anaesthesia. 2005;60(5):439-444.

pubmed doi - Poopalalingam R, Chin EY. Rapid preparation of a patient with pheochromocytoma with labetolol and magnesium sulfate. Can J Anaesth. 2001;48(9):876-880.

pubmed doi - Minami T, Adachi T, Fukuda K. An effective use of magnesium sulfate for intraoperative management of laparoscopic adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma in a pediatric patient. Anesth Analg. 2002;95(5):1243-1244, table of contents.

pubmed - James MF, Cronje L. Pheochromocytoma crisis: the use of magnesium sulfate. Anesth Analg. 2004;99(3):680-686, table of contents.

pubmed - Wong AY, Cheung CW. Dexmedetomidine for resection of a large phaeochromocytoma with invasion into the inferior vena cava. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93(6):873.

pubmed doi - Del Pizzo JJ, Schiff JD, Vaughan ED. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma. Curr Urol Rep. 2005;6(1):78-85.

pubmed doi - Augoustides JG, Abrams M, Berkowitz D, Fraker D. Vasopressin for hemodynamic rescue in catecholamine-resistant vasoplegic shock after resection of massive pheochromocytoma. Anesthesiology. 2004;101(4):1022-1024.

pubmed doi

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism is published by Elmer Press Inc.